The great construction productivity conundrum

Anyone else thinking about construction productivity over the Christmas break? No, maybe it was just me then!

Well, I wasn’t quite thinking about it when I was having my turkey or pulling the Christmas crackers, but I did reflect on some construction productivity reports I read a few weeks ago. I thought it would share some reflections through our The science of Quantik™ weekly publication.

The first relates to a 2021 investigation by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) into productivity growth and its drivers for the UK construction industry. I will summarise some of the salient points within the report before providing my reflections and final thoughts.

Productivity in the construction industry, UK: 2021

The whole economy achieved, between 1997 and 2020, a productivity improvement of 25% whereas the construction industry’s productivity has deteriorated by 10%; a 35% net deterioration (Figure 1). The productivity measure used in this investigation is output generated per unit of output with gross value added (GVA) used as the measure of output and hours worked (or composite measure of labour and capital inputs) as the inputs. This means, in real terms, the construction industry puts in 10% more effort to achieve what it did in 1997.

Figure 1: Output per hour worked, construction industry and sub-industries and whole economy, UK, 1997 to 2020, index 1997 = 100

The data provided at Figure 1 provides an analysis of sub-industries within the construction industry and shows that the construction of buildings is the most significant contributor to the industry’s productivity performance as it has deteriorated by 25% (a 50% net deterioration against the whole economy). This means, in real terms, that 25% more effort is required to construct the same buildings we built in 1997.

These are worrying statistics, but they become even more concerning when set against shifts in education and the significant increase in capital investment within the construction industry.

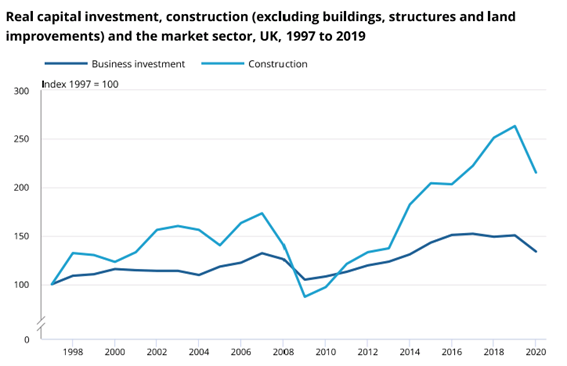

We have more degree educated people working in the construction industry, albeit this trend reflects the whole economy which we lag (Figure 2), and we have seen real capital investment increase by more than 100% which compares favourably against a 40% whole economy increase (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Proportion of total hours worked by highest education qualification, construction and the whole economy, UK, 1997 and 2019

Figure 3: Real capital investment, construction (excluding buildings, structures and land improvements) and the market sector, UK, 1997 to 2019

The relative increases in education levels and capital deepening (investment in technology, machinery, equipment etc) should have a positive effect on productivity because, in theory, businesses have more or better-quality capital available to them.

However, what we are seeing is investment having an adverse impact on productivity (or, at best, stopping it from getting worse), and this is the great construction productivity conundrum.

Reflections

On the face of it, these statistics are shocking, and, when you think about it, do you feel like the environment you work in, or have worked in the past, is as productive as it can be where everything is performing like a well-oiled machine? No, me neither.

If we look at a couple of micro examples, look at email and meeting culture in the construction industry. I can’t say whether we are any different to other industries but trying to solve complex technical issues by email, the “copy all” culture that seems to have perpetuated and be tolerated, and drawn-out meetings attended by way too many where their input is only required for five minutes is not productive whichever way we look at it.

Then think about some wider examples where capital has been invested but I’m not sure we are any better now than we were 20 years ago.

The first is design. The design process was quite linear, and responsibilities were clear cut, for example the architect was responsible the architectural design. When drawings were ready, these were received in 2D and given to the operatives on the front line to construct. The current process is more dynamic and, arguably, cyclical with responsibilities that are grey; does the architect still really own the architectural design anymore? The design is completed in 3D and, from there, 2D drawings are extracted for operatives to construct. I feel like design has become less productive and I can’t see it getting better any time soon.

The second is contract administration. The advent of the NEC contract brought with it a wave of optimism that, suddenly, the construction industry would behave differently just because the contract said it should. This would be achieved through better contract administration. However, to me, what we have achieved is the creation of a contract administration cottage industry where excessive administration is required at all levels of the construction supply chain. I hear the rhetoric about how much better this is but, personally, I’m still not sure what we have solved.

In both cases, we have added cost into project delivery but are we seeing value in the way of productivity improvements or improved building outcomes?

That said, if you look closely at the measure, I’m not convinced it is a true reflection of construction productivity but, rather, it is more of a financial / economic measure. This is because the output used in the measure, and compared against the hours worked, is gross value added which is a financial metric. In simple terms, gross value added is the grand total of all revenues, from final sales and (net) subsidies, which are incomes into businesses. This means that the output is not one that reflects physical output on a construction site but it’s sales price for that work and, as we know, the sales price can have multiple influencing factors.

However, that is not to say that the statistics are wrong, just that they are a bit greyer than they first appear. In saying that there is undoubtedly a link to productivity performance; if a business cannot achieve its required revenue and is not as profitable as it would like to be then it is more than likely to be the case that it is not performing productively.

Improving productivity will go hand in hand with improving profitability.

Final comments

The issues raised in this article only scratch the surface of an issue which, if not fixed, presents an existential threat for existing players in the construction industry; there is no escaping this reality.

I intend to explore further industry reports regarding construction productivity in upcoming The science of Quantik™ publications.

Until then, I would be interested to hear whether you see the world differently? Do you see the need for improvement, and do you have any plans to improve your productivity this year, or that of your team or business?

Back to insights

THE SCIENCE OF QUANTIK™

Publications

We publish insights through our LinkedIn newsletter, titled “The science of Quantik”, which are light bites of information covering news and insights relating to the construction industry and quantity surveying.

LinkedIn